Indus Valley Civilization

No fancy tombs or ziggurats characterized the Indus. However, a uniquely gifted Indus people brought the first urban cities into being cities that accommodated nearly 60,000 to 80,000 people.

While warring kingdoms ruled Egypt and Mesopotamia, a peaceful ideology and harmonious living characterized the Indus. It was a vibrant, diverse civilization with well-planned cities teeming with artisans and widely-traveled merchants. Through a sophisticated network over land and sea routes, a globally connected people exported finely crafted textiles, indigo dyes, carnelian beads and other luxury items to Mesopotamia, Iran, and Central Asia.

What the Indus people explored, learned, and cherished as values and accomplishments, passed on to future generations. Their progressive ideas and vision, and the entrepreneurial spirit, are embraced today, 5,000 years later, on the Indian subcontinent.

|

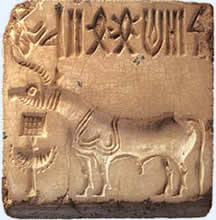

A terra Cotta Cart Of Harrappa .. "The (Harappan) animal seals are among the world's greatest examples of an artist's ability to embody the essentials of a given form in artistic shape." (B. Rowland) The Indus valley civilisation is also called the Harappan culture. Archaeologists use the term �culture� for a group of objects, distinctive in style, that are usually found together within a specific geographical area and period of time. In the case of the Harappan culture, these distinctive objects include seals, beads, weights, stone blades and even baked bricks. These objects were found from areas as far apart as Afghanistan, Jammu, Baluchistan (Pakistan) and Gujarat . Named after Harappa, the first site where this unique culture was discovered, the civilisation is dated between c. 2600 and 1900 BCE. There were earlier and later cultures, often called Early Harappan and Late Harappan, in the same area. The Harappan civilisation is sometimes called the Mature Harappan culture to distinguish it from these cultures. |

The Harappan seal in the above picture is possibly the most distinctive artefact of the Harappan or Indus valley civilisation. Made of a stone called steatite, seals like this one often contain animal motifs and signs from a script that still remains undeciphered.The above seal shows unicorn figure of Indus Valley culture. Whether it designates a real or mythical animal is unknown. Yet a great deal about the lives of the people who lived in the region, is known from what they left behind –their houses, pots, ornaments, tools and seals – in other words, from archaeological evidence.

|

Major Developments in Harappan Archaeology

Nineteenth century

- 1875

- Report of Alexander Cunningham on Harappan seal

Twentieth century

- 1921 M.S. Vats begins excavations at Harappa

- 1925 Excavations begin at Mohenjodaro

- 1946 R.E.M. Wheeler excavates at Harappa

- 1955 S.R. Rao begins excavations at Lothal

- 1960 B.B. Lal and B.K. Thapar begin excavations at Kalibangan

- 1974 M.R. Mughal begins explorations in Bahawalpur

- 1980 A team of German and Italian archaeologists begins surface explorations at Mohenjodaro

- 1986 American team begins excavations at Harappa

- 1990 R.S. Bisht begins excavations at Dholavira

The Plight Of Harrappa

Although Harappa was the first site to be discovered, it was badly destroyed by brick robbers. As early as 1875, Alexander Cunningham, the first Director-General of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), often called the father of Indian archaeology, noted that the amount of brick taken from the ancient site was enough to lay bricks for �about 100 miles� of the railway line between L ahore and Multan. Thus, many of the ancient structures at the site were damaged. In contrast, Mohenjodaro was far better preserved.

The Seals,Script,Weights...

- The Yet to be deciphered Indus Script

The Delphian- Enigmatic Script

Harappan seals usually have a line of writing, probably containing the name and title of the owner. Scholars have also suggested that the motif (generally an animal) conveyed a meaning to those who could not read. Most inscriptions are short, the longest containing about 26 signs. Although the script remains undeciphered to date, it was evidently not alphabetical (where each sign stands for a vowel or a consonant) as it has just too many signs � somewhere between 375 and 400. It is apparent that the script was written from right to left as some seals show a wider spacing on the right and cramping on the left, as if the engraver began working from the right and then ran out of space. Consider the variety of objects on which writing has been found: seals, copper tools, rims of jars, copper and terracotta tablets, jewellery, bone rods, even an ancient signboard! Remember, there may have been writing on perishable materials too. May be this could mean that literacy was wide spread.

Weights:

Exchanges were regulated by a precise system of weights, usually made of a stone called chert and generally cubical , with no markings. The lower denominations of weights were binary (1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, etc. up to 12,800), while the higher denominations followed the decimal system. The smaller weights were probably used for weighing jewellery and beads. Metal scale-pans have also been found.

Agriculture Practice

While the prevalence of agriculture is indicated by finds of grain, it is more difficult to reconstruct actual agricultural practices. Were seeds broadcast (scattered) on ploughed lands? Representations on seals and terracotta sculpture indicate that the bull was known, and archaeologists extrapolate from this that oxen were used for ploughing. Moreover, terracotta models of the plough have been found at sites in Cholistan and at Banawali (Haryana). Archaeologists have also found evidence of a ploughed field at Kalibangan (Rajasthan), associated with Early Harappan levels (see p. 20). The field had two sets of furrows at right angles to each other, suggesting that two different crops were grown together. Archaeologists have also tried to identify the tools used for harvesting. Did the Harappans use stone blades set in wooden handles or did they use metal tools? Most Harappan sites are located in semi-arid lands, where irrigation was probably required for agriculture. Traces of canals have been found at the Harappan site of Shortughai in Afghanistan, but not in Punjab or Sind. It is possible that ancient canals silted up long ago. It is also likely that water drawn from wells was used for irrigation. Besides, water reservoirs found in Dholavira (Gujarat) may have been used to store water for agriculture.

The RULERS

- The Preist King

If we look for a centre of power or for depictions of people in power, archaeological records provide no immediate answers. A large building found at Mohenjodaro was labelled as a palace by archaeologists but no spectacular finds were associated with it. A stone statue was labelled and continues to be known as the �priest-king�. This is because archaeologists were familiar with Mesopotamian history and its �priest-kings� and have found parallels in the Indus region. But as we will see (p.23), the ritual practices of the Harappan civilisation are not well understood yet nor are there any means of knowing whether those who performed them also held political power. Some archaeologists are of the opinion that Harappan society had no rulers, and that everybody enjoyed equal status. Others feel there was no single ruler but several, that Mohenjodaro had a separate ruler, Harappa another, and so forth. Yet others argue that there was a single state, given the similarity in artefacts, the evidence for planned settlements, the standardised ratio of brick size, and the establishment of settlements near sources of raw material. As of now, the last theory seems the most plausible, as it is unlikely that entire communities could have collectively made and implemented such complex decisions.