Peasant turned King - Devi Sigh of Raya Mathura- Unsung Hero of 1857 Revolt

|

| Devi Singh: An Ordinary Peasant to a Self Proclaimed King Challenging the British Authority in His Own Capacity |

When one speaks of 1857 revolt, the first names that strikes us are Jhansi Laxmi Bhai, Nanasaheb and sometimes Tantia Tope. But there were many well established local leaders, and numerous individuals who took up arms on their own initiative without waiting for the Emperor's appeal, or for feudal aristocrats to tell them what to do. Devi Singh was perhaps the quintessential subaltern insurgent, acting entirely on his own without any contact with outsiders. He came from a Jat dominated region centred around the small rural town of Raya in Mathura district.

Some may quip - what is the use of knowing about these forgotten little known of a revolt(?) 200 years back. First it let people know the conditions at that time, the spirit of fighting against oppression and more over it tells the circumstances where leaders have been born out of the "ordinary" and how they sacrifice all they have for the combined cause of the community.

Devi Singh, a village rebel of Tappa Raya in Mathura, had in his biographer his principal enemy, Mark Thornhill, magistrate of Mathura, who wrote the biography for future generations 'as illustrative of native habits and of the condition of the country at that time'. But the political implication of rural rebellion was not altogether lost on even such a biographer. `Dayby Sing's career was brief and in its incidents, rather ludicrous', wrote Thornhill; 'it might have been otherwise. With as small beginnings Indian dynasties have been founded. He was the master of fourteen villages. Runjeet Sing commenced his conquests as lord of no more than twenty-five).

Devi Singh's brief and 'ludicrous career' is important for us because in his rebellion there was no outside intervention or mediation. It was entirely the affair of a peasant community of a small area. Raya, which was included in pargana Mat until 1860 and thereafter in pargana Mahaban, was a busy market town at the centre of a group of villages. It followed the usual pattern of Jat settlement in this area. Raya itself had no arable land. But it was considered 'as the recognised centre of as many as twenty-one Jat villages which were founded from it'. The very name of the town was derived from that of its founder, Rae Sen, the ancestor of the Jats of Godha clan.

The most visible symbol of authority in tappa Raya was an old fort built by Jamsher Beg and renovated by Thakur Daya Ram of Hathras in the early nineteenth century. The latter's control over this area ended with his subjugation by the English in 1817. Still, his family continued to be the dominant magnates in this area and the loyalty of Thakur Govind Singh, his son, in 1857 helped the house to recover much of its old position." During the mutiny Tappa Raya had a police station and tehsil. But more important than that, it was dominated by the Baniyas. Janaki Prasad, Jamuna Prasad, Matilal and Kishan Das were leading mahajans who lived in this town. It was their masonry houses that were 'the most conspicuous buildings in that place', and a 'large orchard of mango and Jaman trees, twenty-two bighas in extent, that adorned the tappa was planted by Kisan Das'. Gokul Dass Seth, who headed a list of prominent mahajans made on the eve of the mutiny, lived in Raya, as did Nanda Ram, head of the rising Baniya family in the region."

When zamindars and villagers in the locality heard of the King of Delhi's proclamation, they rose up against the moneylenders and attacked the town. The prominent face of this Revolt is Devi Singh...

The Story Of Making King

The narrative of Thornhill the District Magistrate is limited to his experience with Devi Singh. For the backgroung behind the Making of King can be found from a small book by Shri Gobind Swarup. The narrative goes like this -

Devisingh a Lord Hanuman follower, once while returning from his daily exercise routine was questioned by a youth wittingly "You have become a Pehalwan by exercising daily. By displaying your strength before us is of no use- if you really have guts, go and fight the Phirangi (British Soldiers)". This pushed Devi Singh in to thinking and he replied - " Brother, what you said is right. But how can I get big army required to fight the British?". One from the crowd was quick to shout " why not make your own Army?". Devi singh nodded in agreement and immediately one more from the crowd adds fuel to the Devi Singh's introspection- " Nodding will do no good. Go and show your strength". Devi Singh replies with full confidence " Yes I will build Army". There started the Jourmey of Devi Singh to build an Army.

Devi singh sells whatever he has to get some money for buying swords and guns. He gathers the village youth and trained them in the warfare. He gets the youth trained in firing the arms by a retired soldier. Slowly Devi singh's army swelled in numbers. Knowing this, the Local Police Officer orders Devi Singh to Join British Army. For which Devi Sigh denies stating " We will not Join English. We will join the Delhi Sultan and save the nation".

Soon Devi Singh with the help of Raja Nahar Singh of Ballabgarh gets Farmaan issued by the Mughal Badshah appointing Devi Singh as the King of Raya Fort.

So getting declared as King, Devi Singh builds Army and tried his best to stop the British Forces in advancing to Mathura during the revolt. He attacks the Mathura Fort, gets hold of the treasury and the arms. He overthrown the local police. The rule of Debi Singh lasted for six months.

The Brief Stint as the KING

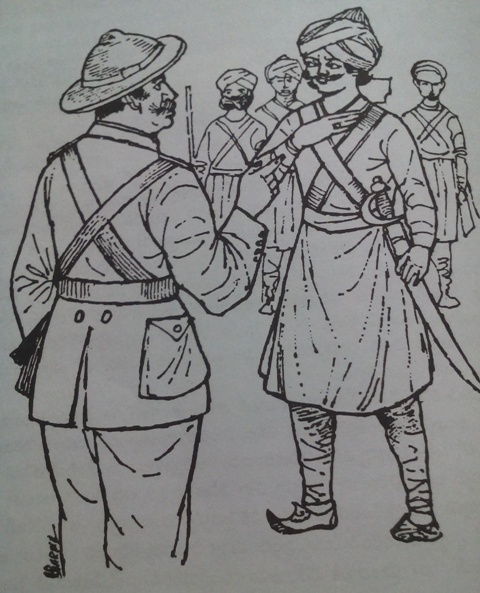

Devi Singh, otherwise a man of no distinction, was dressed in yellow, the traditional symbol of royalty, and declared by popular acclaim to be the jat ‘peasant king' of the 14 villages in the locality. Upon entering the town, he set up a Government upon the English model – thus simultaneously demonstrating the limits of insurgent consciousness at this time, and tried the moneylenders .

But Devi Singh did not reckon with the strength of the empire. To him the colonial state was a local affair and 'having driven out the police he thought he had overthrown our government'. This want of maturity, perhaps historically inevitable, was soon to cost him his life and his little kingdom. For the audacity of the armed peasantry, roused en masse to settle accounts with the Baniyas--the element of local society still loyal to the Raj in 1857—and Devi Singh's expressed intention to drive Thornhill, the district magis¬trate, out of his refuge in an opulent banker's house in Mathura city, prompted the latter to make an example of Raya. On the arrival of the Kotah contingent from Agra to free him from a state of virtual seige, he led it into an attack on the rebel village on 15 June, where he seized Devi Singh and Sri Ram and hanged them. That marked the end of the short-lived counter-Raj in tappa Raya and the beginning of the restoration of colonial authority in the area by early November.'

`Dayby Sing's career was brief, and in its incidents rather ludicrous', wrote Thornhill in concluding his reminiscences of the village raja. This condescension followed to no mean extent from his discovery of the utter ordinariness of his adversary. He was 'a very ordinary-looking man' who, when captured by the counter¬insurgency forces, was hardly distinguishable from the other peasants; the seat of his power was 'an ordinary village, large and very ugly, a mere collection of mud huts closely huddled together'. But it is precisely in such ordinariness, scorned by the administrator turned historian, that the student of Indian history must learn to identify and acknowledge the hallmark of a popular rebel leadership—a leadership which, even when it stands at the head of the masses in a struggle, bears on it all the marks of its emergence out of the ranks of the masses themselves.