Computer that understands your Hand Gestures : MIT

| The below is a youtube video which shows Tom Cruise in the Movie "Minority Report" using interactive UI by using optical Gloves. |

|

|

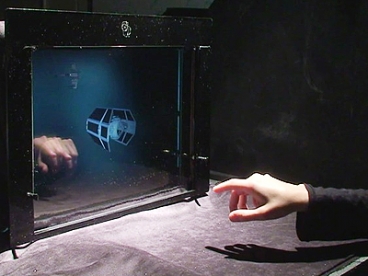

Media Lab researchers demonstrate a laboratory mockup of a thin-screen LCD display with built-in optical sensors. Photo: Matthew Hirsch, Douglas Lanman, Ramesh Raskar,Henry Holtzman Soucre : © MIT |

Remember the scene in ‘Minority Report,’ the Steven Spielberg-directed science fiction thriller, when Tom Cruise uses his hands and

fingers to search for date on a huge virtual screen?Even though the movie came out in 2002, and is set in 2054, it seems as though the present is

catching up to the future. MIT research now comes up almost close to the the futuristic screen of the movie. Means you can also be a

Tom Cruise  Before going into the details, a brief info about the present situation of touch screen computers..

Before going into the details, a brief info about the present situation of touch screen computers..

Windows 7, the follow-up to Windows Vista, comes with a multitouch user interface with the help of 3D desktop BumpTop, which means you can touch the computer screen to perform actions. Touch-based interfaces have captured everyone's imagination, thanks in large part to the iPhone. With Windows 7, Microsoft joins Apple in bringing touch to the desktop, baking touch capabilities into the operating system itself.

And both Apple and Windows are trying for various patents. Here is something more from MIT research. MIT points out a future computer which you can operate by waving Hands.

The iPhone’s familiar touch screen display uses capacitive sensing, where the proximity of a finger disrupts the electrical connection between sensors in the screen. A competing approach, which uses embedded optical sensors to track the movement of the user’s fingers, is just now coming to market. But researchers at MIT’s Media Lab have already figured out how to use such sensors to turn displays into giant lensless cameras. On Dec. 19 at Siggraph Asia — a recent spinoff of Siggraph, the premier graphics research conference — the MIT team is presenting the first application of its work, a display that lets users manipulate on-screen images using hand gestures.

Many other researchers have been working on such gestural interfaces, which would, for example, allow computer users to drag windows around a screen simply by pointing at them and moving their fingers, or to rotate a virtual object through three dimensions with a flick of the wrist. Some large-scale gestural interfaces have already been commercialized, such as those developed by the Media Lab’s Hiroshi Ishii, whose work was the basis for the system that Tom Cruise’s character uses in the movie Minority Report.

But “those usually involve having a roomful of expensive cameras or wearing tracking tags on your fingers,” says Matthew Hirsch, a PhD candidate at the Media Lab who, along with Media Lab professors Ramesh Raskar and Henry Holtzman and visiting researcher Douglas Lanman, developed the new display.

Some experimental systems — such as Microsoft’s Natal ( Click Here to Visit Xbox Natal's Project Page; Click here for CNET news article on Natal) — instead use small cameras embedded in a display to capture gestural information. But because the cameras are offset from the center of the screen, they don’t work well at short distances, and they can’t provide a seamless transition from gestural to touch screen interactions. Cameras set far enough behind the screen can provide that transition, as they do in Microsoft’s SecondLight,(Click Here for a PDF about Microsft SecondLight from Microsoft Website) but they add to the display’s thickness and require costly hardware to render the screen alternately transparent and opaque. “The goal with this is to be able to incorporate the gestural display into a thin LCD device” — like a cell phone — “and to be able to do it without wearing gloves or anything like that,” Hirsch says.

The Media Lab system requires an array of liquid crystals, as in an ordinary LCD display, with an array of optical sensors right behind it. The liquid crystals serve, in a sense, as a lens, displaying a black-and-white pattern that lets light through to the sensors. But that pattern alternates so rapidly with whatever the LCD is otherwise displaying — the list of apps on a smart phone, for instance, or the virtual world of a video game — that the viewer never notices it. LCDs with built-in optical sensors are so new that the Media Lab researchers haven’t been able to procure any yet, but they mocked up a display in the lab to test their approach.

Like some existing touch screen systems, the mockup uses a camera some distance from the screen to record the images that pass through the blocks of black-and-white squares. But it provides a way to determine whether the algorithms that control the system would work in a real-world setting. In experiments in the lab, the researchers showed that they could manipulate on-screen objects using hand gestures and move seamlessly between gestural control and ordinary touch screen interactions. Of the current crop of experimental gestural interfaces, “I like this one because it’s really integrated into the display,” says Paul Debevec, director of the Graphics Laboratory at the University of Southern California's Institute for Creative Technologies, whose doctoral thesis led to the innovative visual effects in the movie The Matrix.

“Everyone needs to have a display anyway. And it is much better than just figuring out just where the fingertips are or a kind of motion-capture situation. It’s really a full three-dimensional image of the person’s hand that’s in front of the display.” Indeed, the researchers are already exploring the possibility of using the new system to turn the display into a high-resolution camera. Instead of capturing low-resolution three-dimensional images, a different pattern of black-and-white squares could capture a two-dimensional image at a specific focal depth. Since the resolution of that image would be proportional to the number of sensors embedded in the screen, it could be much higher than that of the images captured by a conventional webcam.

Raskar, who directs the Media Lab’s Camera Culture Group, stresses that the work has even broader implications than simply converting displays into cameras. In the history of computation, he says, “intelligence moved from the mainframe to the desktop to the mobile device, and now it’s moving into the screen.” The idea that “every pixel has a computer behind it,” he says, offers opportunities to reimagine how humans and computers interact.